Designing for Participation and Power

The Data & Design Group’s mission is to envision a world where everyone has the power to shape the design of systems that affect their social and political lives. We do this by working with people and communities to co-design new technologies in the domains of data accessibility and ethics. This post explains the perspective that informs our work in disability inclusion and public interest technology. We characterize this perspective as an orientation toward participation and power.

Managing Participation, A Core Dilemma for Technology and Society

As technology becomes more integrated into people’s lives, it has the capacity to shape participation in society. Problems arise when groups of people are systematically excluded by technology design. This idea is clearest in the domain of accessibility. Blind and low-vision (BLV) people are typically excluded from using websites that are not designed for the screen reader assistive technology that they use to narrate visual content as text-to-speech. Consequently, BLV people face barriers to their ability to participate in conversations and make decisions about about socially important issues. For example, researchers have found that about 97% of state websites in the U.S. that provided information about the COVID-19 pandemic had significant accessibility problems in 2021. It is important to note that the challenge here is not simply that designers are ignorant of the need for accessibility. For instance, companies have attempted to develop AI-powered tools to make web content more accessible. Yet, blind and low-vision users and disability advocates have pointed out that “the fix can be worse than the flaws” when these tools make websites even less usable. When designers lack knowledge on how to meaningfully address accessibility issues, imperfect solutions can be worse than doing nothing. The challenge, especially for researchers, is to discover how to meaningfully address accessibility through design.

But perhaps counterintuitively, inclusion can also be harmful — for instance, when technology includes people in social processes that they find coercive or disagreeable. This is commonplace in the domain of data ethics. The public has become unfortunately accustomed to data scandals like Cambridge Analytica, in which many Facebook users’ data was repurposed for political influence campaigns — sometimes without any action on their part. Similarly, users’ data is often repurposed and used to train facial recognition systems that are frequently sold to the police to power state surveillance, or directly sold by data brokers which can power discriminatory credit scoring or stalking and harassment. As a consequence of these commonplace practices, people who do not agree with the repurposing of their data for certain uses do not have the power to influence the process or withdraw their participation. Here, challenges abound in addressing people’s fundamental lack of agency over their data.

Two Case Studies from the Data & Design Group

In our work, we’ve found that thinking about problems through a lens of participation and power enables us to identify important opportunities to make a difference.

Accessible Data Analysis

As institutions increasingly rely on data visualization to communicate important information visually—from election results to COVID-19 case rates—lack of equitable information access for blind and low vision people excludes many from participating fully in public life. Although over 7 million people in the U.S. have a visual disability according to the National Federation of the Blind, a recent study found that 96.8% of web pages fail to meet basic standards for making content accessible to screen readers (an assistive technology that narrates text and visual media as speech).

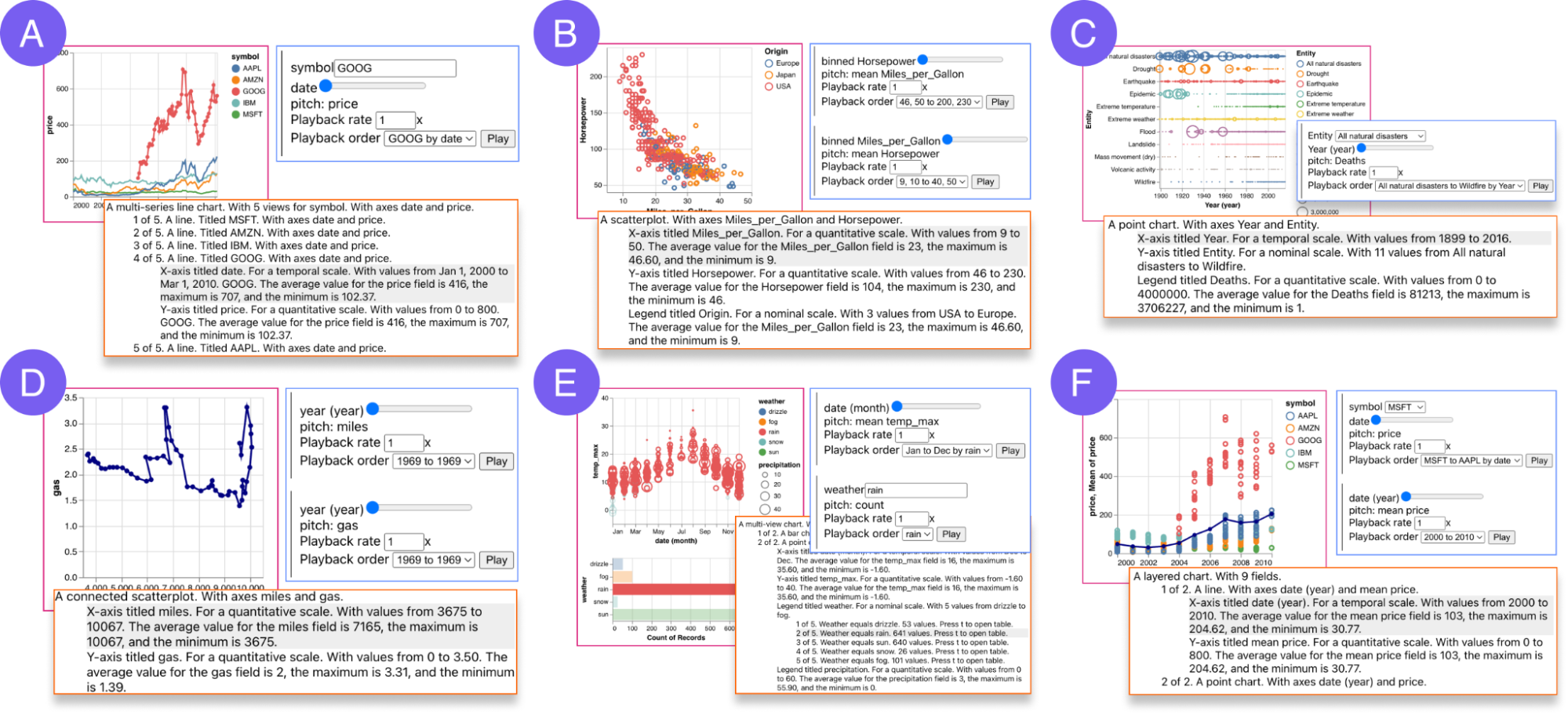

In response, we developed Olli, an open source system that transforms data visualizations into keyboard-navigable structures that offer text descriptions of data at varying levels of detail. With this software, screen reader users who encounter visualizations can read an initial summary of the chart, and optionally navigate into the chart to explore sub-sections in more detail. Analogously to how sighted people inspect different regions of a chart by shifting their perceptual attention, Olli enables screen reader users to selectively seek information.

Prior to this work, best practices for accessible visualization involved providing textual description in a summary paragraph and providing a data table that a screen reader user could read row-by-row. But these approaches do not provide modes of information-seeking comparable to what sighted readers enjoy with interactive visualizations. Systems like Olli instead offer keyboard-navigable structures of multiple descriptions at varying levels of detail, affording user agency over the reading order and level of information granularity in each description. This work has encouraged researchers (including at CMU, Microsoft, and Tableau) to reconceptualize textual description as a fundamentally interactive modality.

When we reflected on our conversations with BLV folks about why it was important for them to get access to data, we recognized that making existing charts accessible was only the first step in enacting information equity. Instead of only being consumers of charts created by sighted people, what would it take for BLV people to be producers of data representations?

This led us to create Umwelt: an accessible tool for screen reader users to create their own data representations that include visualization, interactive text, and sonification. Prior systems for creating non-visual data representations often required an existing visualization to convert into an accessible form. We recognized that this created additional barriers for BLV users who needed to translate their intended non-visual designs into visual terms. With Umwelt, screen reader users are able to edit multisensory outputs through a common abstraction in the editor, reducing their dependency on sighted colleagues to do data analysis and interpretation.

Ethical Data Collection

When social and behavioral research primarily happened in lab settings, people were generally always aware of their status as research participants; but as this research moved online to social media platforms, people are now included in data collection by default — frequently without their knowledge. This newfound possibility of passive participation in research has required researchers to apply ethics procedures in new ways. For instance, online studies reduce the viability of prior informed consent: a scientist studying online speech during a political debate cannot predict in advance who will participate in conversations during the event.

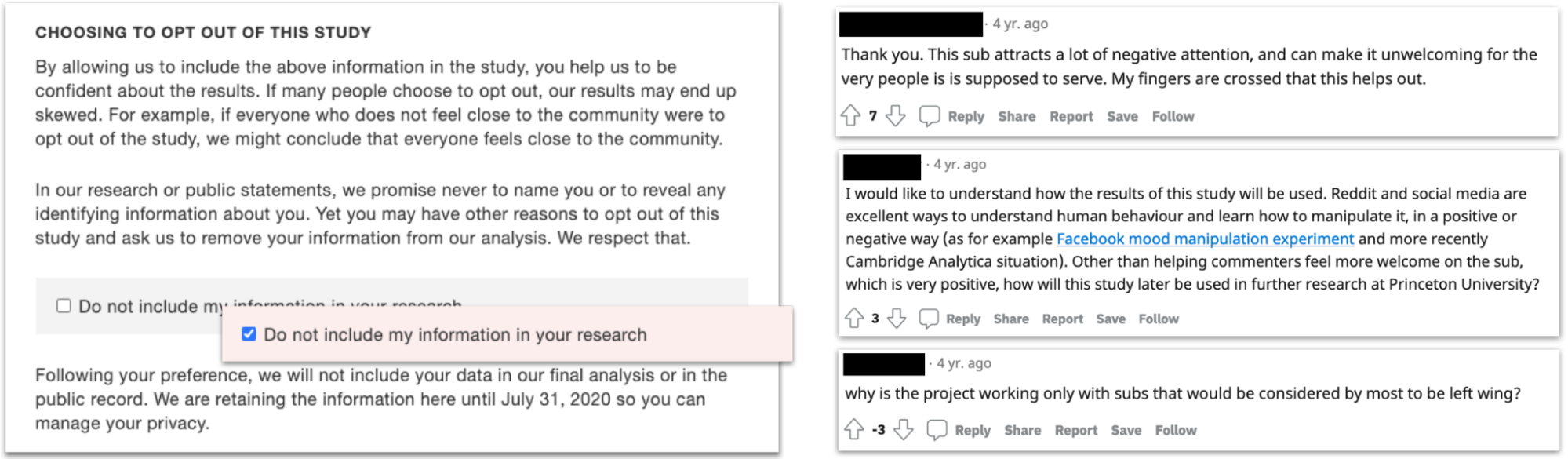

In response, we developed Bartleby, a system for automatically notifying data subjects after data collection and directing them to a web interface where they have a chance to opt out by deleting their data. Bartleby takes a procedure known as debriefing, historically used in deception-based lab studies, and applies it in a new context online. We tested Bartleby in two studies on Twitter and Reddit. In these cases, Bartleby promoted participant autonomy by creating an option where there wasn’t one before. It also opened a communication channel between participants and researchers, enabling conversations about values that would not otherwise have happened.

Computer scientists have historically lacked a framework for understanding opt-outs as an expression of user voice and agency; instead, computer scientists often assume that non-users will become future users with improvements to technology design. A consequence of this assumption is that non-users are considered either passive resources to be mined for design ideas, or problems to be solved through design. Our work puts forth an alternate view, arguing that refusal can be understood as a generative act of socio-technical design.

Because people refuse to change an existing situation into a preferred one, refusal in the form of active non-participation in a system is actually an important way to influence a design process toward desired outcomes. Crucially, the idea of refusal as design empowers computer scientists to apply the methods of design to understand refusal. Though refusal might initially seem to be the opposite of generative design, computer scientists equipped with an understanding of refusal as design can see refusals as a healthy and necessary part of a socio-technical design process that can inspire directions for systems-level change.

Participation and Power as a Unifying Lens for Design

Though these two domains of accessible data analysis and ethical data collection are seemingly separate, the idea of participation and power provides an underlying conceptual grounding that unites our approach to both sets of problems.

In accessible data analysis, many BLV users are in a state of disempowered non-participation due to the design of their software tools — they are fully excluded from conversations about data due to a lack of knowledge in the design community about how to design effective non-visual data representations and interactions. In this domain, we aims to help people move toward a state of empowered participation.

Conversely, in ethical data collection, people are often in a state of disempowered participation for reasons relevant to design — they are included in large-scale data collection processes in which software tools do not respect their individual autonomy, and are unable to exert structural influence that would shift the goals of the data collectors toward alternatives they find more agreeable. In this domain, our work aims to help move people toward a state of empowered non-participation.